Diving into the past: underwater worlds in ancient Eastern Mediterranean culture

In the age of dramatic ecological changes, it is more important than ever to understand how different human cultures have engaged with their environment, not only today, but also in the past. As two-thirds of the surface of the Earth is covered by marine waters, marine ecosystems are one of the most interesting areas of exploration. Centuries of human activity focused around seas and oceans may be key to our ability to better appreciate and protect the oceans around and beneath us.

Dr. Mari Yamasaki is an archaeologist specialising in the pre- and protohistory of the eastern Mediterranean basin. In particular, her scientific interests revolve around the relationship between humans and the sea, both above and below water. Her project, UnReal: Underwater realms. Concepts of underwater spatiality in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean is aimed to explore the conceptualization of underwater spaces and to analyze the relationship between underwater and terrestrial spaces in maritime representations: Project: Underwater realms. Concepts of underwater spatiality in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean

For over two years of her research, Dr. Yamasaki studied late Minoan maritime-themed larnakes and Archaic Greek maritime depictions. Larnakes are burial containers made of clay but designed to imitate wooden chests. Her work involved cataloging these objects, mapping recurring iconographic elements, and positioning them in a database for network analysis (Nodegoat.net).

The findings from Minoan Crete showed that underwater conceptualization was primarily centered on marine life, with fishes, dolphins, and octopi dominating the imagery. Less frequently, clams and argonauts appeared. Waterfowl, often decorating the lids or upper registers of larnakes, also played a role in this conceptualization. The interior of the larnax represented the submerged realm, while the exterior signified dry land. Additionally, the positioning of figures on larnakes mirrors real-life aquatic observations, with the larnax itself acting as a material metaphor for the underwater world. In the case of bathtub-shaped larnakes, the entire composition appears designed to simulate immersion in the sea, reinforcing the idea that maritime larnakes functioned as metaphorical sea burials. This suggests that in Minoan thought, underwater spaces had a dual character: as a real, observable environment inhabited by marine creatures and as a symbolic netherworld.

Network analysis also revealed diachronic and geographical shifts in underwater conceptualization. While the early representations (1600-1150 BCE) were centered in Crete, later depictions (8th-7th century BCE) shifted to mainland Greece and its colonies in Anatolia and Italy. By this period, maritime imagery increasingly featured human figures, often in perilous situations such as shipwrecks, drownings, or being devoured by fish. Unlike Minoan representations, which emphasized marine biodiversity, these later depictions focused on fear and danger, portraying underwater creatures as menacing. This shift reflects cultural anxieties surrounding sea travel and the impossibility of proper funerary rites for those lost at sea. To be devoured by fish was seen as a curse that extended beyond death, reinforcing the conceptualization of the sea depths as a realm of horror.

These contrasting modes of depicting aquatic spaces stem from differences in experiential weight: the Minoan focus on routine maritime activities like fishing and gathering versus the Greek emphasis on rare but traumatic shipwrecks.

Regarding the relationship between land and underwater environments in constructing imagined underwater spaces, the study highlighted a significant grey zone – representations that blend real experiences with imagined elements. Not all underwater depictions derive solely from direct observations; often, they borrow extensively from terrestrial environments. Many underwater realms are mirrored versions of the world above but are generally accessible only to gods, heroes, and the dead.

By integrating cognitive and network analysis methodologies, UnReal successfully traced these evolving conceptualizations, providing new insights into how ancient societies visualized and understood the underwater world. Until recently, archaeological research on human engagement with the underwater spaces was deemed unrealistic, the long-standing reasoning being that we lacked sufficient evidence for such activities. On the contrary, this project not only demonstrated that there are far more sources on ancient diving than it was assumed, but also prepared the grounds for a fully-fledged archaeology of freediving.

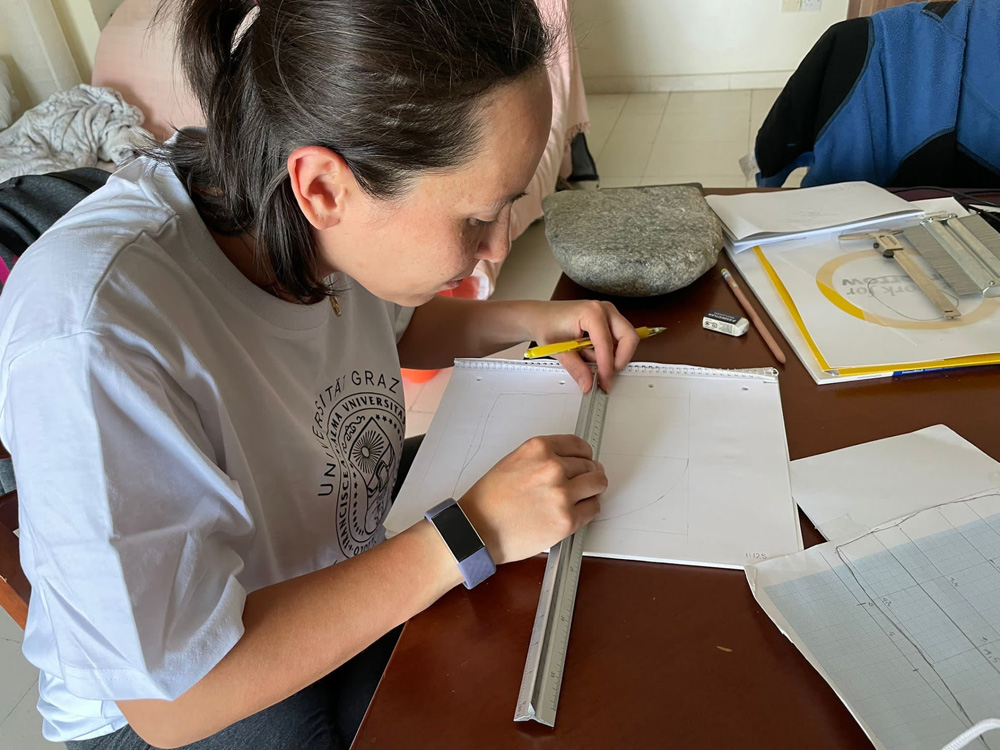

“As an archaeologist, fieldwork is a fundamental component of my work” – says dr. Yamasaki. Archaeological fieldwork is the systematic excavation, survey, and documentation of past human activity. Researchers carefully excavate layers of soil to uncover artifacts, structures, and ecofacts. Fieldwork requires meticulous recording through notes, drawings, photographs, and digital tools to preserve contextual information. Ethical considerations, including site preservation and community engagement, are also crucial.

Dr. Mari Yamasaki documenting her work

“Our excavation at Erimi-Pitharka (Cyprus), directed by prof. Lærke Recht of Moesgaard Museum and dr. Katharina Zeman-Wiśniewska of the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, is situated close to the village and we were often visited by passersby and curious residents. A very satisfying and enriching part of our job in the field is to engage with our spontaneous visitors and illustrate what, why and how we are digging and to involve the local population in discovering and protecting their cultural heritage” – dr. Mari Yamasaki describes her research activities.

Dr. Mari Yamasaki at the archaeological site

According to her “Engaging with the public does not stop after excavation and I think it is of capital importance to improve the way archaeologists in general and myself in particular communicate with the public”. For this reason, during her international secondment she spent about a month and a half at the Museum for Ancient Navigation (Museum für antike Schiffahrt), a part of the Leibniz Zentrum für Archäologie in Mainz, Germany. She had an opportunity to join the educational department in preparing exhibitions and guided tours for the general public, and to design specific workshops and activities for the younger visitors: “Working with children was especially challenging and rewarding, and proved to be a huge learning experience” – she notices.

Finally, an essential part of her job as a researcher was to present the research outcomes to both her colleagues and to the public. In these two years, she has attended several international conferences and was invited to hold guest lectures internationally (Copenhagen, Belfast, Graz) and in Poland (Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology “Underwater realms – imagining and conceptualizing the sea as a 3D space” ).